Not very far from London, in the English county of Hertfordshire, lies an unusual wheat field.

The wheat grown here has been genetically edited to reduce the amount of acrylamide it contains once cooked, as that compound is believed to increase the risk of cancer.

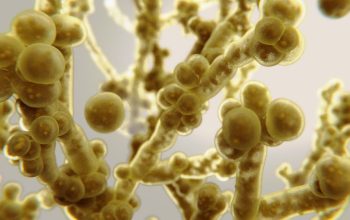

To achieve this, plant and crop scientists at Rothamsted Research edited out a gene that produces a compound called asparagine.

Asparagine occurs naturally in plants and is also present in other starchy foods like potatoes and other tubers.

But when wheat is processed into flour and turned into a baked product like bread, asparagine turns into another compound called acrylamide, which is carcinogenic in very large doses.

Reducing the amount of asparagine in wheat grain would therefore mean less acrylamide in toast, cereal, and biscuits, and lower cancer risk in other cooked foods containing wheat.

So far, the trials have seen a 50 per cent reduction in asparagine and a 50 per cent reduction in acrylamide in heated flour.

“That’s really exciting and positive, but it’s only one year of field trials,” said Professor Nigel Halford, a crop scientist leading the trial at Rothamsted.

“We have to see how they come through in terms of yield, protein content, that kind of thing over a number of years, then we would make these available to breeders”.

The wheat grown in this field will be finally assessed after it’s harvested in October.

The acrylamide in burnt toast

Acrylamide wasn’t a new compound for scientists because it’s used in industrial processes, but it was only discovered in 2002 that it could occur in heavily toasted or browned starchy foods.

“It’s a familiar chemical to biochemists, we use it in the lab,” said Halford.

“You can take acrylamide out of a bottle, it’s got a skull and crossbones on it. So to discover that you then go over to the canteen and you eat it, it was quite a shock,” he explained.

However, it doesn’t mean that eating burnt food will give people cancer, scientists caution, because the dose from food is very small.

Studies linking acrylamide to cancer have only been carried out in animals, using much higher doses than we would ingest through eating.

But our genetic makeup is unique and our bodies will respond differently to the risk.

The aim of genetically edited wheat is therefore to reduce any risk, overall.

Concerns around GMOs

So far GM foods are not cleared for consumption in the EU or the UK.

But Halford says the UK and the EU are now considering changing the “benchmarks” which guide how much acrylamide is an acceptable risk in foods.

He also highlighted that the wheat growing in the Hertfordshire field was genetically edited, not genetically modified (GM).

“These are edited plants, no transgenes in, no genes from other species, no additional genes at all. It is not a GM plant,” said Halford.

Using the CRISPR gene-editing process, he and his team extracted a tiny fragment of tissue from the grain which was then grown and fed in a petri dish.

A “gene gun” was then used to fire DNA into the cells and remove genetic traits affecting the amount of asparagine present in the wheat.

In the UK, a law that would allow the commercial production of genetically-edited wheat has reached its final stage through parliament.

The legislation, called the Genetic Technology Precision Breeding Bill, is now awaiting royal assent.

For more on this story, watch the video in the media player above.

Video editor • Roselyne Min