The upcoming presidential elections in Montenegro are set to be a make-or-break moment for the country’s political future.

Ljubomir Filipović, an analyst and former deputy mayor of Budva, told Euronews that “these presidential elections should not be taken lightly, despite the limited powers of the president in Montenegro.”

The country is split between two blocs — one that supports the country’s pro-European stance and another that leans toward Russia. This divide has led to frequent protests in the past three years.

However, recent events in Montenegro have made these elections even more crucial. In August 2020, the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS) was removed from power, and a coalition of nationalist and civic-minded parties formed a government, which has since been restructured twice.

Although Montenegro declared its independence from Serbia in 2006, it still struggles to shake off Serbia’s attempts to influence its politics, particularly through the Orthodox Church.

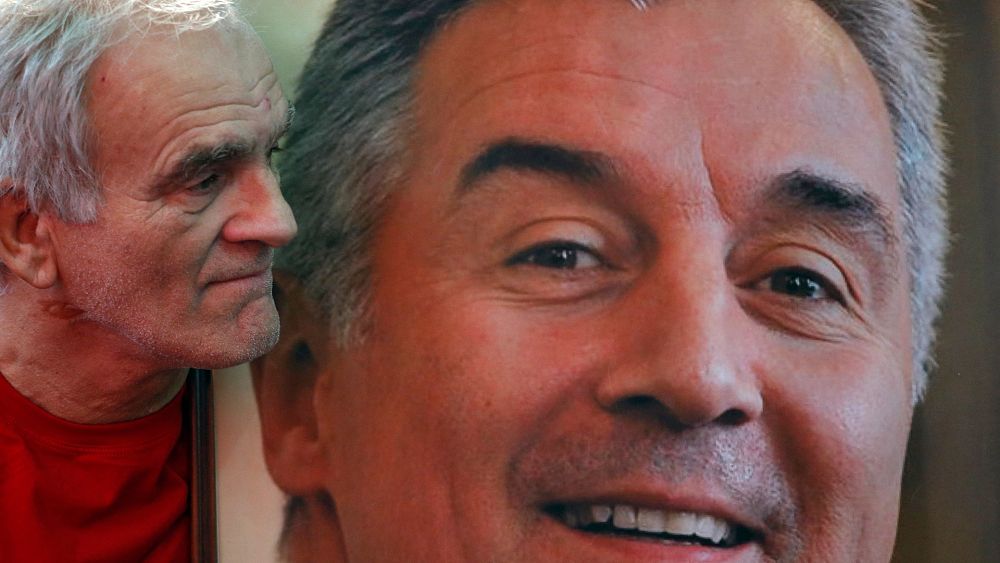

Milo Đukanović, the incumbent president and DPS leader, played a pivotal role in organising the referendum for independence and has branded himself as the sole defender of Montenegro’s sovereignty and pro-Western path.

In the presidential race, one of his opponents is Andrija Mandić from the eurosceptic Democratic Front, a party that openly advocates for closer ties with Russia and Serbia.

Filipović points out that this is not just a battle between Đukanović and his opponents, but a fight between two ideologies in Montenegro.

He said that “while Đukanović represents corruption, organised crime, captured institutions, and a tendency towards political monopolisation on one hand, he also represents opposition to those questioning Montenegro’s independence and sovereignty as a nation.”

“Those who are against Đukanović do not represent a strong enough opposition to the influence of Serbia and Russia in the country, especially through the Orthodox Church,” he emphasised.

Battle between two churches

The fight for control and influence over the religious and political landscape of Montenegro has been shaped by the ongoing feud between the Serbian Orthodox Church (SOC) and the Montenegrin Orthodox Church (MOC).

The Serbian Orthodox Church, which is closely aligned with the government in Belgrade and the Kremlin, has been accused of interfering in Montenegro’s politics and spreading pro-Serbian propaganda.

The Montenegrin Orthodox Church, which split from the Serbian Orthodox Church in 1993, has accused its counterpart of trying to undermine its independence.

The fight boiled over in 2019 when the Montenegrin government passed a law that would transfer ownership of religious properties from the SOC to the state.

The SOC saw this as an attempt to strip them of their influence and rallied their supporters, held protests, and even encouraged their followers to boycott the Montenegrin census, claiming that it was biased against them.

On Thursday, Đukanović issued a decree to dissolve parliament, days before the election and as the three-month legal deadline expired for former top diplomat and prime minister-designate Miodrag Lekić to form a government.

Recent iterations of the government, at one time led by Prime Minister Dritan Abazović from the green-civic URA party, have been notoriously soft on the SOC’s influence in the country, and the results of the presidential elections will dictate how the next government will handle this sensitive issue.

Not enough new blood

Jovana Marović, a respected civil society member, was part of the URA party and government but recently resigned from her positions due to policy disagreements.

She warned that both leading candidates in the election, including Đukanović and Mandić, could pose a challenge to the country’s democratic processes.

“The biggest problem is that not a single one of the candidates is a civic option,” she told Euronews.

Marović recalls that it was during Đukanović’s previous stints as prime minister and foreign minister that the country’s institutions were brought to their knees due to cronyism and corruption.

“Elections are always important in the Western Balkans because they define the general direction the country is headed. These elections come at a time when the country is experiencing a deep political crisis, and the results could significantly influence the democratic processes in the country,” she continued.

The third front-runner, Jakov Milatović, is a young economist from the increasingly popular Europe Now Movement. His party was not in the parliament and a win for him could bolster the party’s results in the parliamentary elections.

Montenegro is a frontrunner in its European integration process and how the upcoming elections shape up could influence the speed with which it progresses on this path.

Although the country has completed most of its duties on the technical level, the unreformed justice sector remains a challenge due to high polarisation in society, Marović stressed.

“On the other hand, the fact that there have been several government rotations after 30 years of what was effectively one-party rule. This is the healthiest way of strengthening a country’s democratic reflexes,” she concluded.