Twenty years after the US-led invasion of Iraq, the country remains mired in corruption, political instability and violence.

According to OPEC, the Organisation of Oil Exporting Countries, Iraq has the world’s fourth largest reserves after Venezuela, Saudi Arabia and Iran. But the country’s citizens see little benefit, with power cuts commonplace in many parts of the country.

Billions of dollars worth of revenue is either syphoned off through corruption or fail to reach the national coffers.

Militias continue to dominate parts of the country and the creation of lasting and stable governments is proving elusive.

High youth unemployment leaves millions of people with little prospect for the future.

“Iraqi youth have made it clear in recent years that they don’t want to have a regime that is divided along religious lines,” said political scientist Asiem El Difraoui, of the Candid Foundation in Berlin.

“They don’t want to have a regime that only works through clientelism, corruption, politics, but there is a new form, especially among younger people, of Iraqi nationalism.”

However, there is also a brain drain, with many young Iraqis leaving the country, many with painful memories of childhoods marked by terror and bloodshed.

The agency AFP interviewed Zulfokar Hassan, who was born two years before the American-led invasion.

He was a young child when his mother woke him in the middle of the night so they could hide in the bathroom during a US forces raid in their Baghdad neighbourhood.

“The houses around us were collapsing,” he recalled about the battle on September 6, 2007, when US helicopters and tanks targeting Shiite militants killed 14 civilians in the Al-Washash district.

The next day, the seven-year-old boy looked around the rooftop terrace where the family usually slept in the blistering summer months.

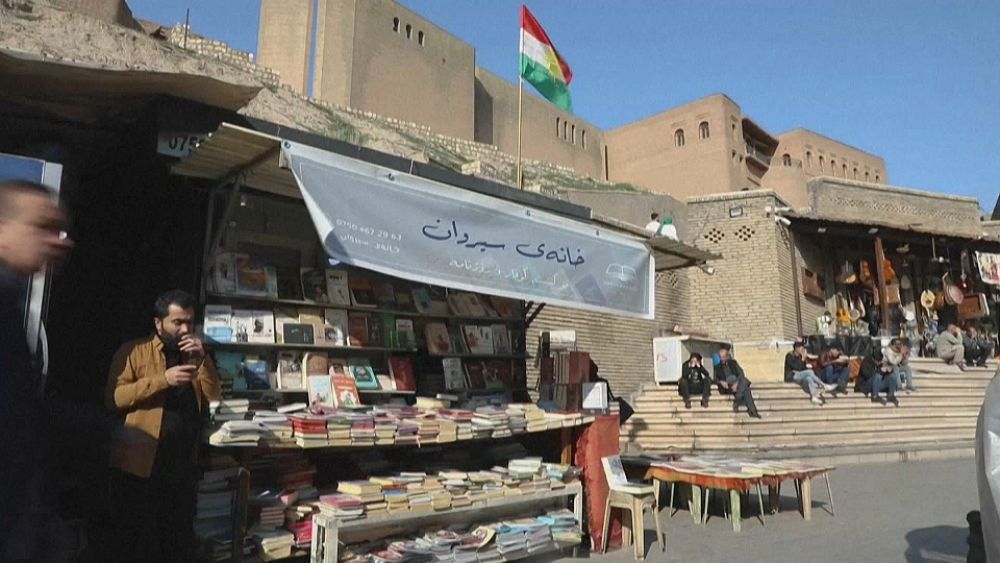

“There was shrapnel, our mattresses were burned,” recalled Hassan, now a calligraphy student.

Like many from his generation, he tells his story in the detached tone of someone for whom street battles, car bombs and corpses lying on the road were the tragic backdrops of daily life.

“Throughout our childhood we were terrified,” he said. “We were afraid to go to the toilet at night, no one could sleep alone in a room.”

One of his uncles has been missing since 2006. He left in his car to shop for food and never came back.

In late 2019, Zulfokar joined the sweeping, youth-led demonstrations against endemic misrule and corruption, crumbling infrastructure and unemployment.

“But I stopped,” he said, recounting the crackdown that killed hundreds. “I had lost hope. I saw young people like me dying, and we were helpless.

“Martyrs have been sacrificed, without result and without change.”

Despite this, he said he has no plans to emigrate, as so many other disillusioned Iraqis have. Otherwise, he asked, “who would be left?”